There were a few points of this week's reading regarding management games that I'll mention in this post.

Management games are focused on getting the player to take charge of multiple elements at one time, this could be things like resource management or time managent. Trefry mentioned time frequently in this chapter which emphasised to me what the integration of time limitations in management games can do to the overall experience. For example games like Diner Dash and Cake Mania, two examples that Trefry uses in the chapter, both have time management as a constant throughout the game. This adds a level of intensity that cannot be found in other management games such as Insaniqarium, forcing the player to micromanage more frequently, making it further swayed toward the hardcore gamer, however whilst still maintaining its casual elements.

Another factor of management games that although not mechanic related is important, is a simple means of interaction and navigation. In management games players need the ability to make choices and carry out those decisions quickly, making an easy to use interaction mechanic a fairly essential aspect of these types of games. Management games that implement this well can allow players to concentrate on managing as opposed to exogenous factors like clicking a mouse or pressing buttons on a keyboard.

Trefry, like in previous chapters, mentioned the intuitiveness that surrounds management games. I got into a slightly side tracked chat with my girlfriend just after I read the chapter about whether she reckoned that playing Diner Dash would help her should she become a waitress. Tayla is a bit of an Diner Dash fan and she studies criminal psychology at Birmingham Uni, so she had some psychological jargen to throw at me about it. Last year I read an article by Costikyan where he established that a game is "...an interactive structure of endogenous meaning that requires players

to struggle toward a goal.” So this point isn't completely unjustified. I argued that having that cognitive strength regarding management/ time management skills or 'plate spinning' ability, would be transferable to a real life scenario as a waitress. Tayla however argued that it wouldn't be the same as in a real life waitressing job you're managing your tasks over a longer period of time as well as managing spontaneous tasks that may throw you off track. For example, once a player has played Diner Dash enough they can begin to learn all of the micromanagement tasks that run seperate to keeping the customers happy, however in real life, there may be variables that differ on a daily basis, a spilt drink or a broken glass. Also a waitress only deals with the customers a few times over the space of an hour/hour and a half, which requires a different type of mental ability to playing Diner Dash as this ventures into the realms of involving your long term memory. Apparently, on average your short term memory lasts between 5-10 seconds and can retain 7 +/- 2 chunks of information, making Diner Dash a good indication of the strength of your short term memory.

So... I wondered if a possible iteration to Diner Dash would to better simulate the waitressing profession and have the waiting table aspect of the game to play a less central role. So maybe if placing the customers, taking their order, serving them, clearing the plates and giving the bill came into play over a longer period of time and in between carrying out those tasks the player had to micromanage themselves into completing other waitressing related tasks. This could be tasks like washing plates and stacking them away, clearing dust/dirt from the restaurant floor. I'm not sure whether waitresses/waiters actually carry out these jobs during their shifts but I'm sure there are other tasks they are assigned that could be converted into different mechanics in a game. This way players would be demanded to remember and manage their tasks/time not just on a short term basis but also their ability to remember and manage over long periods. It could also break up the repetition of carrying out the same clicking mechanic.

Although it seems so, the above point isn't completely off on a tangent, Trefry mentiones in the chapter that adding additional tasks on top of core tasks can add additonal layers of complexity to increase difficulty for the player. He also adds that complexity should be gradually introduced allowing players to adjust their pattern of play to adapt to these new challenges.

I don't have much more to pull out of the chapter, these were the more important points that I found.

Sunday, 30 October 2011

Monday, 24 October 2011

Weekend Paper Prototyping

At the weekend, Adam, Matt and I decided that making our level for the Modding module would be a fun challenge. To reiterate, our level is based on an Egyptian dig site and composed of two floors. The upper is the digsite, which is designed to be open long spaces for longer range conflict. The bottom (the focus of our paper prototype) is a an excavated tomb, which uses more confined spaces designed for concentrated battles. We felt that this would be the best floor to prototype as it would allow us to test the shapes of corridors and hallways.

So below are the images of our development of the protoype. We have yet to begin testing the spaces by experimenting with obstacles, that will most probably take place during the week however we have all the space laid out ready to do so.

I've done a few visualisations as an example of the kind of thing we are going to use the prototype for in our design document.

We started by drawing out the floorplan based on our initial idea, beginning to take into consieration scale. We estimated that roughly 15mm = 1meter in game, which is a bit of an odd scaling system but we were catering around how big we could make the map on an A1 sheet.

We cut it out... Not as good as we could have done might I add, due to an old scalpel and that we were cutting on the underside of my rug...

We had to elevate the floor as we have a section of recessed floor in the main chamber, which you can see in this image.

I then added the staircase incline which is one of the entrances down into the tomb, you can see this on the far right of the image.

Alongside this we added the ramped floor next to the entrance of the tomb which leads to a drop down to the outer walkways. We also added a central pillar to represent the large statue that will take its place in game.

Visualisations

These are examples of how I expect some of the spaces to be used in game. We haven't added the sloped path down to the recessed flooring yet either, however in the final version this will be implemented.

You can see form the bottom image that we haven't built in the slopes yet however if you refer to the map that I've posted earlier on in my blog (keep scrolling down) you should be able to see where they are going to be placed.

So this is about 85% finished however I thought i'd blog it now as I'm going to be short on time over the next week. After seeing it like this I'm more confident about the design of our map overall, just need to do a decent job of modelling it digitally now!

Again if you would like to see the original floorplan it is in this month's postings, so just scroll down.

So below are the images of our development of the protoype. We have yet to begin testing the spaces by experimenting with obstacles, that will most probably take place during the week however we have all the space laid out ready to do so.

I've done a few visualisations as an example of the kind of thing we are going to use the prototype for in our design document.

We started by drawing out the floorplan based on our initial idea, beginning to take into consieration scale. We estimated that roughly 15mm = 1meter in game, which is a bit of an odd scaling system but we were catering around how big we could make the map on an A1 sheet.

We cut it out... Not as good as we could have done might I add, due to an old scalpel and that we were cutting on the underside of my rug...

We had to elevate the floor as we have a section of recessed floor in the main chamber, which you can see in this image.

I then added the staircase incline which is one of the entrances down into the tomb, you can see this on the far right of the image.

Alongside this we added the ramped floor next to the entrance of the tomb which leads to a drop down to the outer walkways. We also added a central pillar to represent the large statue that will take its place in game.

Visualisations

These are examples of how I expect some of the spaces to be used in game. We haven't added the sloped path down to the recessed flooring yet either, however in the final version this will be implemented.

You can see form the bottom image that we haven't built in the slopes yet however if you refer to the map that I've posted earlier on in my blog (keep scrolling down) you should be able to see where they are going to be placed.

So this is about 85% finished however I thought i'd blog it now as I'm going to be short on time over the next week. After seeing it like this I'm more confident about the design of our map overall, just need to do a decent job of modelling it digitally now!

Again if you would like to see the original floorplan it is in this month's postings, so just scroll down.

Sunday, 23 October 2011

Casual Game Design: Seeking

I've never been a massive fan of seeking games, mainly because my patience seems to wear thin whenever I'm sitting staring at the same space for one object. Trefry doesn't give seeking games an exactly shining review either.

He suggests that seeking, like sorting and matching, is an instinctive proccess, with which I'd agree. Man has been seeking for hundreds of thousands of years, its a suvival instinct. This instinctivity supports seeking games as a solid foundation from which to build casual games. They require no explanation as all humans are familiar with the concept of finding hidden objects. Trefry points out that seeking games offer no replayability, once a player has discovered the object, or the route from A to B, the game becomes useless. Unless of course a game like find the ball under the cup is being played. However games like that require no logical thought proccess or strategy to allow the player to find what they are looking for, making seeking games fairly unsatisfactory even after completion.

One method that Trefry suggests is trying to implement logic into seeking games to try and add a sense of accomplishment, other than just persisting to seek until you eventually complete the game. He uses a few examples in the chapter, none that I can talk confidently about having not played them, however the game 'Crimson Room' I have played. This is a game where the player is locked in a room and is left no instructions as to how to escape, they must rely on their seeking abilities to help them. Logic is integrated into Crimson Room in that the player must find an object in order to interact with another object in order to progress. For example, finding the key under the bed that will open the box on the shelf, which contains a shard of glass that can be used to cut a hole in the wallpaper. Even though this is just a glamourised version of seeking, players can begin to feel like they are using some form of problem solving, which can create an overall stronger sense of satisfaction. What's also a nice little extra to Crimson Room is that there is a snippet of narrative given at the beginning of the game, which isn't much but helps the player immerse themselves in the dilemma.

Other than pointing out the few flaws in seeking and potential improvements to it Trefry doesn't expand much further, and I don't think much more needs to be said either. I'll finish this post with a link to Crimson Room so you can see if you agree with what Trefry or I feel about seeking games.

He suggests that seeking, like sorting and matching, is an instinctive proccess, with which I'd agree. Man has been seeking for hundreds of thousands of years, its a suvival instinct. This instinctivity supports seeking games as a solid foundation from which to build casual games. They require no explanation as all humans are familiar with the concept of finding hidden objects. Trefry points out that seeking games offer no replayability, once a player has discovered the object, or the route from A to B, the game becomes useless. Unless of course a game like find the ball under the cup is being played. However games like that require no logical thought proccess or strategy to allow the player to find what they are looking for, making seeking games fairly unsatisfactory even after completion.

One method that Trefry suggests is trying to implement logic into seeking games to try and add a sense of accomplishment, other than just persisting to seek until you eventually complete the game. He uses a few examples in the chapter, none that I can talk confidently about having not played them, however the game 'Crimson Room' I have played. This is a game where the player is locked in a room and is left no instructions as to how to escape, they must rely on their seeking abilities to help them. Logic is integrated into Crimson Room in that the player must find an object in order to interact with another object in order to progress. For example, finding the key under the bed that will open the box on the shelf, which contains a shard of glass that can be used to cut a hole in the wallpaper. Even though this is just a glamourised version of seeking, players can begin to feel like they are using some form of problem solving, which can create an overall stronger sense of satisfaction. What's also a nice little extra to Crimson Room is that there is a snippet of narrative given at the beginning of the game, which isn't much but helps the player immerse themselves in the dilemma.

Other than pointing out the few flaws in seeking and potential improvements to it Trefry doesn't expand much further, and I don't think much more needs to be said either. I'll finish this post with a link to Crimson Room so you can see if you agree with what Trefry or I feel about seeking games.

http://www.albinoblacksheep.com/games/room

Chime Review

I thought I'd break up readings with a small post about my thoughts on a game I've recently purchased, Chime. I should start by saying that I do think that the idea behind Chime is pretty cool, I think it's a nice idea, however I was expecting more from the concept.

Chime is a 'tetris-esque' type of game in that players place different shaped blocks in order to create squares (or quads as they're called in game). The bigger the quads the bigger the points you make. From the description so far Chime is an adaptation of tetris. However the twist that Zoë Mode (the developers behind Chime) have integrated is a mechanic that involves using sound and the players' block positioning to create different compositions. I should also say that to each level there is a different track composed by a different artist that plays through the entirety of the level.

There is also a line that runs from left to right, sweeping across your placed blocks. As the line crosses the blocks a note is played that is in the same key as the track being played, so consequently creating a new song depending on how you placed you blocks.

I'm not expecting you to get it from by bad description but if you follow the the Youtube link below then hopefully with my description you'll get it:

There has been alot of hype surrounding Chime, pre and post release, about it's synergy between music and gameplay. I would completely agree that there is a certain relation between the two, however for me music and choices made in game aren't related.

From a musical perspective I'm sure Chime is a really cool way of recomposing songs and adding elements that weren't originally intended. Although from a gameplay perspective, after a few hours of playing Chime, I failed to see how a simple gamer like me could get involved properly with creating my own unique composition. I found that my choices in game were influenced only by the shapes of the blocks I was handed, much alike they would be had I been playing Tetris. I keep mentioning Tetris however I don't want to give off the impression that I'm undermining the efforts put into developing Chime or attempting to be flippant and having a 'Oh it's basically Tetris with music' attitude, because I'm not. I'm just stating that there is a relation between the two in that you are placing blocks to form shapes for points.

As I was saying, my choices were influenced in the same way that they would be had I been playing Tetris. I think this was mainly because my score was cumulated based only on my block positioning, so I felt no need to focus on the musical aspect of it. The musical element was quite a nice feature, but again it had no effect on my progress or scoring. For me that wasn't really enough. I did a little test and tried playing Chime with my sound muted, and found that I placed my blocks in the same way that I would had it not been muted, which I think was the same time I started to lose enthusiasm for Chime. Perhaps this relates to what Trefry was saying about the hardcore expecting complexity from casual games, maybe my score based mentality was blinkering me from enjoying the music that I created, so perhaps I'm being too tough.

However, personally I think that a nice iteration to Chime would be to add some kind of composition bonus, or something that would link the music to the scoring. Perhaps if players' placed blocks in a certain way that corresponded to techniques used in creating melodies or tunes in music. For example if a player organised their blocks in a sort of zigzag shape then that would create a vibrato and that would add a multiplier or maybe just extra points to you current score. Or if the player arranged the blocks to create an inclined/declining shape then that would play a melody using a scale that would compliment the song. I'm not an expert in music so I can't reel off a load of different shapes and potentially related musical techniques, but I'm sure there are other means of doing so. This for me would help to create a stronger bond between block positioning and the music that the player was making. This was the sort of thing that I was expecting of Chime originally, a way for a non-musically educated person like me to get involved in creating their own tune combined with the block placing mechanic. I understand that this game isn't solely based on composing music, however after listening to all the hysteria that followed Chime I think I felt a bit cheated into buying and playing it.

I think the best thing to do to demonstrate what I'm saying is to play Chime, you can get it off of the Xbox live arcade and I think it's available from the Playstation store as well. Buy it if you're not put off by my review, give it a go and see if it works for you.

Chime is a 'tetris-esque' type of game in that players place different shaped blocks in order to create squares (or quads as they're called in game). The bigger the quads the bigger the points you make. From the description so far Chime is an adaptation of tetris. However the twist that Zoë Mode (the developers behind Chime) have integrated is a mechanic that involves using sound and the players' block positioning to create different compositions. I should also say that to each level there is a different track composed by a different artist that plays through the entirety of the level.

There is also a line that runs from left to right, sweeping across your placed blocks. As the line crosses the blocks a note is played that is in the same key as the track being played, so consequently creating a new song depending on how you placed you blocks.

I'm not expecting you to get it from by bad description but if you follow the the Youtube link below then hopefully with my description you'll get it:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B11LXvmraus&feature=related

There has been alot of hype surrounding Chime, pre and post release, about it's synergy between music and gameplay. I would completely agree that there is a certain relation between the two, however for me music and choices made in game aren't related.

From a musical perspective I'm sure Chime is a really cool way of recomposing songs and adding elements that weren't originally intended. Although from a gameplay perspective, after a few hours of playing Chime, I failed to see how a simple gamer like me could get involved properly with creating my own unique composition. I found that my choices in game were influenced only by the shapes of the blocks I was handed, much alike they would be had I been playing Tetris. I keep mentioning Tetris however I don't want to give off the impression that I'm undermining the efforts put into developing Chime or attempting to be flippant and having a 'Oh it's basically Tetris with music' attitude, because I'm not. I'm just stating that there is a relation between the two in that you are placing blocks to form shapes for points.

As I was saying, my choices were influenced in the same way that they would be had I been playing Tetris. I think this was mainly because my score was cumulated based only on my block positioning, so I felt no need to focus on the musical aspect of it. The musical element was quite a nice feature, but again it had no effect on my progress or scoring. For me that wasn't really enough. I did a little test and tried playing Chime with my sound muted, and found that I placed my blocks in the same way that I would had it not been muted, which I think was the same time I started to lose enthusiasm for Chime. Perhaps this relates to what Trefry was saying about the hardcore expecting complexity from casual games, maybe my score based mentality was blinkering me from enjoying the music that I created, so perhaps I'm being too tough.

However, personally I think that a nice iteration to Chime would be to add some kind of composition bonus, or something that would link the music to the scoring. Perhaps if players' placed blocks in a certain way that corresponded to techniques used in creating melodies or tunes in music. For example if a player organised their blocks in a sort of zigzag shape then that would create a vibrato and that would add a multiplier or maybe just extra points to you current score. Or if the player arranged the blocks to create an inclined/declining shape then that would play a melody using a scale that would compliment the song. I'm not an expert in music so I can't reel off a load of different shapes and potentially related musical techniques, but I'm sure there are other means of doing so. This for me would help to create a stronger bond between block positioning and the music that the player was making. This was the sort of thing that I was expecting of Chime originally, a way for a non-musically educated person like me to get involved in creating their own tune combined with the block placing mechanic. I understand that this game isn't solely based on composing music, however after listening to all the hysteria that followed Chime I think I felt a bit cheated into buying and playing it.

I think the best thing to do to demonstrate what I'm saying is to play Chime, you can get it off of the Xbox live arcade and I think it's available from the Playstation store as well. Buy it if you're not put off by my review, give it a go and see if it works for you.

Play Is The Thing

Another post based on chapter three of Casual Game Design. The theme of this chapter was 'play' and the enjoyment of it in games.

There were a a few aspects of the chapter that caught my eye. One of the first was the emphasis on pulling out the enjoyable mechanics of a game and refining and developing it. This seems a completely logical method of creating a game that works. In doing this the designer is helping himself to discard the grey areas of his game and moving towards a product that will be as a whole more engaging for the player. Again it links in to the idea of 'killing your babies', in that a designer needs to build up an understanding of what does and doesn't work and have the ability to keep and chuck away both.

Another was Trefry's acknowlegdment of play in every day aspects of our lives. This is something that previously I had never really thought about, yet I myself did it. Trefry gave the examples like 'How much stress can it take before it breaks?, how far can I throw this?'. This relates to humans instinct to creating some form of structured play, for example I tend to click my pen whenever I'm holding it. That in itself is play, not so much consciously or deliberately however it demonstrates Trefry's point.

I think this is a key aspect of game design that should be tapped into more often, especially in casual game design. using play mechanics that come instincively to the player is a good method of establishing a 'pick up and play' feel to your game. A perfect example of what I'm talking about is one of the first apps that I downloaded for my iPhone, Papertoss. The game is fairly self explanatory, players throw paper balls into a bin across a room. The mechanic used in game is a finger motion used to simulate a throwing motion, which is something that we are all familar with. Within a few throws players can begin to get a feel for the physics involved, which again is exactly what you want from a casual game, a short learning curve with quick results.

Trefry also mentioned in Chapter three about the evolution of 'casual' and 'hardcore', about how as player skill and familiarity with games grows, the boundaries for casual game complexity expand. He says something that I'm not sure I entirely agree with, perhaps due to misenterpretation I'm not sure. He states "...The casualness versus hardcore nature of a game is entirely contextual and changes as players evolve and grow more skilled..." Initially I thought that Trefry was saying that casual gaming complexity is increasing as the age of casual gaming increases, regardless of the players and their ability. However as he says 'is entirely contextual' I'm assuming he means that hardcore players who would play casual games would expect a higher difficulty than those who play casual games alone, so the complexity of the casual game is based on your demographic. So the hardcore perceive casual differently to casual gamers, which makes sense.

He continues to break down play into catagories like Attunement play, Object play (like pen clicking), social play, imaginative, solitary play (play involving yourself, reading, collecting) etc. He also mentions that there lies a problem with simple games, in that there will liely be players with naturally stronger 'nacks' for it. For example running, there are clearly individuals who are stronger runners in life than others. The problem with running is that that is the sole skill that allows you to win and doesn't allow for other less talented players to compensate in other areas. Maybe it would be an interesting challenge to iterate the 100m sprint to give others like me a chance of winning!

My final point about the chapter relates to a quote from Trefry that I liked saying, "Games require some level of uncertainty informed by choice..."the reason why I liked this is that it supports and arguement that I used in a discussion about how games like Magic: The Gathering are luck based games. Yes, the outcome of the game is heavily influenced by luck of the draw however it's the players' strategies based on the cards they are dealt that can win or lose the game for them. In my opinion it has just the right amount of uncertainty to allow it to be different each game but also allows enough room for choices and strategy to make you feel like the win (or lose) was down to you. Also your opponent is playing under the same rules, so the choices that you make may not always create a certain outcome that you envisaged, depending on the choice and luck of their turn, which consequently causes you to adapt your choices once again.

Ive skimmed over alot of the chapter but I've picked out the small sections that I found most interesting.

There were a a few aspects of the chapter that caught my eye. One of the first was the emphasis on pulling out the enjoyable mechanics of a game and refining and developing it. This seems a completely logical method of creating a game that works. In doing this the designer is helping himself to discard the grey areas of his game and moving towards a product that will be as a whole more engaging for the player. Again it links in to the idea of 'killing your babies', in that a designer needs to build up an understanding of what does and doesn't work and have the ability to keep and chuck away both.

Another was Trefry's acknowlegdment of play in every day aspects of our lives. This is something that previously I had never really thought about, yet I myself did it. Trefry gave the examples like 'How much stress can it take before it breaks?, how far can I throw this?'. This relates to humans instinct to creating some form of structured play, for example I tend to click my pen whenever I'm holding it. That in itself is play, not so much consciously or deliberately however it demonstrates Trefry's point.

I think this is a key aspect of game design that should be tapped into more often, especially in casual game design. using play mechanics that come instincively to the player is a good method of establishing a 'pick up and play' feel to your game. A perfect example of what I'm talking about is one of the first apps that I downloaded for my iPhone, Papertoss. The game is fairly self explanatory, players throw paper balls into a bin across a room. The mechanic used in game is a finger motion used to simulate a throwing motion, which is something that we are all familar with. Within a few throws players can begin to get a feel for the physics involved, which again is exactly what you want from a casual game, a short learning curve with quick results.

Trefry also mentioned in Chapter three about the evolution of 'casual' and 'hardcore', about how as player skill and familiarity with games grows, the boundaries for casual game complexity expand. He says something that I'm not sure I entirely agree with, perhaps due to misenterpretation I'm not sure. He states "...The casualness versus hardcore nature of a game is entirely contextual and changes as players evolve and grow more skilled..." Initially I thought that Trefry was saying that casual gaming complexity is increasing as the age of casual gaming increases, regardless of the players and their ability. However as he says 'is entirely contextual' I'm assuming he means that hardcore players who would play casual games would expect a higher difficulty than those who play casual games alone, so the complexity of the casual game is based on your demographic. So the hardcore perceive casual differently to casual gamers, which makes sense.

He continues to break down play into catagories like Attunement play, Object play (like pen clicking), social play, imaginative, solitary play (play involving yourself, reading, collecting) etc. He also mentions that there lies a problem with simple games, in that there will liely be players with naturally stronger 'nacks' for it. For example running, there are clearly individuals who are stronger runners in life than others. The problem with running is that that is the sole skill that allows you to win and doesn't allow for other less talented players to compensate in other areas. Maybe it would be an interesting challenge to iterate the 100m sprint to give others like me a chance of winning!

My final point about the chapter relates to a quote from Trefry that I liked saying, "Games require some level of uncertainty informed by choice..."the reason why I liked this is that it supports and arguement that I used in a discussion about how games like Magic: The Gathering are luck based games. Yes, the outcome of the game is heavily influenced by luck of the draw however it's the players' strategies based on the cards they are dealt that can win or lose the game for them. In my opinion it has just the right amount of uncertainty to allow it to be different each game but also allows enough room for choices and strategy to make you feel like the win (or lose) was down to you. Also your opponent is playing under the same rules, so the choices that you make may not always create a certain outcome that you envisaged, depending on the choice and luck of their turn, which consequently causes you to adapt your choices once again.

Ive skimmed over alot of the chapter but I've picked out the small sections that I found most interesting.

Saturday, 22 October 2011

Gregory Trefry: Responsibilties of a Game Designer

Over the weeks that I've been back I've left my blog collecting dust so consequently I have several topics that I would like to cover. I'll be methodical and start with what I missed first.

The first is a reading from the book 'Casual Game Design' by Gregory Trefry regarding the responsibilities of a Game Designer. This section of the book acted, in a sense, as a list of commandments that should be considered when designing games. Trefry spoke in fair detail about consideration for the player and general rules relating to design however I've condensed the content down into less elaborate smaller sentences.

Listen to your team/players. Prototype. Don't be afraid of chucking out ideas that don't work.

These were the more general ideas relating to design that trefry touched upon, all of which make sense. I think the hardest to achieve out of all of these for me is the third. It can be quite difficult sometimes to abandon an idea that you feel so sure will contribute positively to the game, even when initial playtests insist that it won't. This is something that Trefry touches upon later in the book, however he suggests that iterating an idea sometimes loses to persistence in refining one. He does also mention that having the experience to make those kinds of calls is pretty vital, so for now for me iterative design proccess is the way forward.

Trefry then goes on to discuss level design.

Take into account player learning curves and skill levels. Be empathetic. Don't make it too hard. Ease the players into the game. Don't forget to challenge the player. Build levels around a core concept. Give players room to explore. Vary levels. Refine, play, refine. Playtest.

Alot of these may seem fairly obvious but all of the above are worth remembering. For me the most important two here are 'Don't forget to challenge the player. Build levels around a core concept.' Without being pedantic about the definition of 'challenge', a game with no challenge has the potential to become a very boring game. Players like to be challenged, some more than others however in every game there are different magnitudes of a struggle.

From experience, having a core concept in a project can make or break your success in terms of producing a well polished final piece. This is an essential factor to consider, not in just game design but in every arts based subject. At time in the past I've been talking to people about ideas for a project or ideas for final pieces and just thought 'Why?'. I like to think I'm fairly open minded but sometimes I'll hear of a concept that was produced on no more than personal preference without any regard to how it's justified, and can't help but think '....that's stupid...'. It's probably bad of me to say that but, honestly, I'm sure you can think of a few games, art peices, campaigns that are, without dancing around it, shit. I know I've been guilty of it in the past at times, and know how hard it is to try and scrape together any arguements that will help explain why I'm doing something. So as a summary, by coming up with a sound idea/concept, it makes the rest of the project alot easier in all aspects.

The rest of the article included ideas about exploration of mechanics. Not being repetitive. Progression of difficulty. Practice iteration on small games, then get bigger.

I know that not all games stick to these guidelines however I think Trefry writes these with the assumption that the reader/game designer has some eye for design and the ability to know when and when not to consider these as responsibilties. Overall I thought the reading was a nice general topic to kick start the year with and a nice refresher of my responsibilties as a game designer.

The first is a reading from the book 'Casual Game Design' by Gregory Trefry regarding the responsibilities of a Game Designer. This section of the book acted, in a sense, as a list of commandments that should be considered when designing games. Trefry spoke in fair detail about consideration for the player and general rules relating to design however I've condensed the content down into less elaborate smaller sentences.

Listen to your team/players. Prototype. Don't be afraid of chucking out ideas that don't work.

These were the more general ideas relating to design that trefry touched upon, all of which make sense. I think the hardest to achieve out of all of these for me is the third. It can be quite difficult sometimes to abandon an idea that you feel so sure will contribute positively to the game, even when initial playtests insist that it won't. This is something that Trefry touches upon later in the book, however he suggests that iterating an idea sometimes loses to persistence in refining one. He does also mention that having the experience to make those kinds of calls is pretty vital, so for now for me iterative design proccess is the way forward.

Trefry then goes on to discuss level design.

Take into account player learning curves and skill levels. Be empathetic. Don't make it too hard. Ease the players into the game. Don't forget to challenge the player. Build levels around a core concept. Give players room to explore. Vary levels. Refine, play, refine. Playtest.

Alot of these may seem fairly obvious but all of the above are worth remembering. For me the most important two here are 'Don't forget to challenge the player. Build levels around a core concept.' Without being pedantic about the definition of 'challenge', a game with no challenge has the potential to become a very boring game. Players like to be challenged, some more than others however in every game there are different magnitudes of a struggle.

From experience, having a core concept in a project can make or break your success in terms of producing a well polished final piece. This is an essential factor to consider, not in just game design but in every arts based subject. At time in the past I've been talking to people about ideas for a project or ideas for final pieces and just thought 'Why?'. I like to think I'm fairly open minded but sometimes I'll hear of a concept that was produced on no more than personal preference without any regard to how it's justified, and can't help but think '....that's stupid...'. It's probably bad of me to say that but, honestly, I'm sure you can think of a few games, art peices, campaigns that are, without dancing around it, shit. I know I've been guilty of it in the past at times, and know how hard it is to try and scrape together any arguements that will help explain why I'm doing something. So as a summary, by coming up with a sound idea/concept, it makes the rest of the project alot easier in all aspects.

The rest of the article included ideas about exploration of mechanics. Not being repetitive. Progression of difficulty. Practice iteration on small games, then get bigger.

I know that not all games stick to these guidelines however I think Trefry writes these with the assumption that the reader/game designer has some eye for design and the ability to know when and when not to consider these as responsibilties. Overall I thought the reading was a nice general topic to kick start the year with and a nice refresher of my responsibilties as a game designer.

Saturday, 1 October 2011

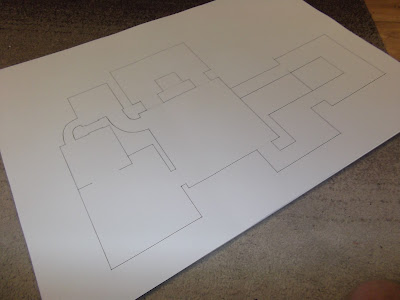

Mod Map Draft

A rough layout of my group's map for our modding module. On the left is the tomb layout and on the right the digsite situatied on top of the tomb. We wanted two different play spaces, one which was fairly open with oppurtunities for longer ranged firefight and the other to be alot tighter for more condensed battles. This is just an initial layout with no accurate scaling to it so it will most likely change over the coming weeks.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)